Here comes the tricky part. Who needs the Quickie-Mart? Often identifying hidden premises and conclusions can require a little more cognitive effort than we have so far had to use in identifying explicit premises and conclusions. Before we look at some helpful interpretive

An implied premise is an unstated reason or claim that supports and is generally required to support the main claim of the argument (i.e., the conclusion). For example consider the following simple argument: We should ban GMO crops because they aren't natural. The stated premise is "GMO crops aren't natural" and the stated conclusion is "therefore we should ban GMO crops." But notice that there is an unstated general premise lurking in the dark that supports the stated premise. It is, "we should reject foods that aren't found in nature." If we decomposed the argument it'd look like this:

Key:

HP1 We should reject foods that aren't found in nature.

P2 GMO crops aren't natural.

MC Therefore, we should ban GMO crops.

HP1 means "hidden premise"

The Vong diagram would look like this:

HP1 + P1-->MC (I.e., linked premises)

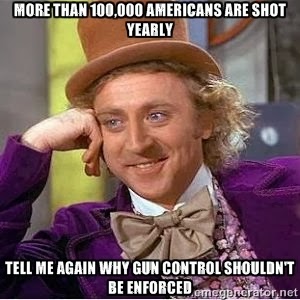

As you may have guessed by now, a hidden/implied conclusion is a conclusion that is not explicitly stated but supported by the premises. Hidden or implied conclusions are almost always (but not exclusively) contained in advertising or editorial cartoons.

Lets look at another example:

Your chances at winning the lottery are slim to none. And slim just left town.

The implied conclusion is that you have (virtually) no chance of winning the lottery.

P1 Your chances at winning the lottery are slim to none.

P2 And slim just left town.

HMC Therefore, you have virtually no chance of winning the lottery.

Vong Diagram

P1+P2-->MC ("+" means linked premises)

General Heuristics: Principles of Communication

For most of you, picking out the hidden premises and conclusions in these examples probably wasn't too difficult. Of course, in real life (and on exams) things usually aren't so easy. What we need are some heuristics to help increase our odds of identifying the unstated parts of arguments. So, lets take a step back and to get a big picture view of what's happening. It will help us devise strategies.

Before moving on, I should quickly note that these principles of communication apply not only to written and spoken arguments. They apply to any type of communication, whether it be a facial expression, movie, piece of art, cartoon, advertisement, hand gesture, etc... If you want to impress you friends, these types of communication are called speech acts.

Given that speech acts are any act or medium that conveys information, we are going to creatively name the three principles of interpretation "principles of communication."

Principle I: Intelligibility

This one's pretty simple. You should assume that a speech act is intelligible. This means that we should assume that it is an attempt to convey something meaningful. It is not just random noise (despite our opinion of the view being expressed).

Principle II: Context

This principle tells us to interpret a speech act relative to its context. For example, is it in response to an opposing speech act? What is the social or political context? Suppose you're walking to class and a young woman offers you a red bull and tells you that it will give you wings. Should we interpret the speech act as the woman's earnest desire for you to have wings or is this an argument for you to buy the product? (Hint: It's not the first choice).

If we examine the context of the speech act, it should be fairly obvious that we should interpret it as an argument. There may be one or more possible contexts within which to frame a speech act: to choose, refer back to principle I: which context makes the speech act more intelligible?

Principle III: Components

So far we've established that a speech act is intelligible and we've interpreted it in a way that fits the context in which we find it. Now, we're going to get a bit more fine grained at look at its components and their relationship to each other. Recall that a speech act can be composed of images, words, gestures, and even interpretive dance (my favorite!). Lets look at an example using images and words:

Applying principle 1 we assume that there is some sort of intelligible message being conveyed. Applying principle II, from the context (someone's facebook page) we might reasonable assume this is an argument for being more cautious about what we consume. Finally, applying principle III we look at the components. There are the words "rethink your drink" and images of sugar and popular drinks. Putting these components together we can formulate the elements of the intended argument: Lots of sugar is bad for you (premise). These drinks have a lot of sugar (premise). Therefore, we should be more careful about what we consume (and how much).

Even though the above image doesn't contain an explicit argument, if we apply the 3 principles of communication we can pick one out and identify the premises and conclusion.

Identifying Hidden Conclusions

Hidden conclusions are most commonly found in short passages or in image-based speech acts (magazine ads, billboards, political cartoons, etc...). OK, now that we know where to find them, how do we identify hidden conclusions?

Method 1

Ask yourself, (a) do the remarks or images imply some sort of point of view? (look at context) In other words, does the information provided propose a conclusion that is unstated? (b) what is this speech act trying to convince me of? (what's it trying to get me to believe, do, endorse?) If it's not trying to convince you of anything, chances are it isn't an argument, but if it is trying to persuade you of something, then it's an argument and you can be darn sure there's a conclusion! (E.g., "buy product x").

Lets look at an example:

Here we have a speech act that, assuming principle I, is an intelligible message. Applying, principle II we might interpret it as an argument (because it's making a controversial assertion). And applying principle III we can identify elements: The image is of a healthy looking community being "eaten away." It's a metaphor for cancer. Given the context and the words we can interpret the premises and conclusion: Growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of cancer (stated premise). Cancer is bad (hidden premise). Capitalism has the same ideology--growth for the sake of growth (hidden premise implied by the picture). Therefore, capitalism is bad (hidden conclusion).

Method 2

Method 2 is similar to method 1 except it's a bit simpler. To identify a hidden conclusion (a) first figure out what the main issue is then (b) determine what position on that issue the arguer wants to convince you of.

Lets consider an example:

"Killing people as punishment doesn't teach them anything." Analysis: (a) What's the main issue? Whether killing people as punishment is a good thing or whether we ought to do it. (b) What position does the arguer seem to take? The seem to be against it so the hidden/implied conclusion would be (HC) Therefore, we shouldn't kill people to punish them OR more generally, we should abolish capital punishment.

Example 2:

Analysis:

What's the main issue? Whether modern technology makes us anti-social. Given the evidence provided, what's the arguers position on the issue? Modern technology doesn't make us any more anti-social than the technology of the past.

Identifying Hidden Premises

How do we identify hidden premises? One mechanical way to do it is to write down the explicit premises and conclusion and see if the argument is intelligible. That is, can we reasonably infer the conclusion from the premises? If not, then there are hidden premises. In other words, there are unstated reasons or claims that the argument depends on. As a charitable person (and good critical thinker) it's up to you to fill in the blanks.

For example, in the previous image if we hadn't filled in the unstated premises, the conclusion wouldn't make sense. It only makes sense if we include (the obvious) hidden premise that cancer is bad. This may be trivial in this particular argument, but hidden premises are sometimes very important and underpin the strength of the entire argument. This relates to a second point about hidden premises.

Frequently, when we evaluate an argument, it is the hidden premises that are good fodder for criticizing the argument. Consider the "anti GMO" argument I gave in the beginning. The hidden premise is that "non-natural food is bad." The argument depends on this being true. If we can find counter-examples then the argument is in trouble. The argument is also in trouble if there is little or no evidence to support the hidden premise.

Caveat: As we've discussed earlier every argument makes many assumptions. You simply cannot possibly state everything you are assuming. What are stated and what are unstated assumptions will depend in large part on what is considered reasonable by the specific audience to which the argument is targeted (and hopefully for a general audience).

Why does this matter? Because you should be judicious in identifying hidden premises. Instead of willy-nilly identifying what are painfully obvious things that are assumed by the arguer, you should expend your effort picking out the hidden premises that are required in order to infer the conclusion from the stated premise. In other words, it doesn't do you much good to identify and criticize trial unstated premises (ah ha! the arguer assumes that people don't like getting punched in the face!).